By Gareth Hoskins, Geography and Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University

Looking back on the workshop last week one of the main things to strike me was our almost inbuilt assumption that heritage is good by default, that there should be more of it, and that we should (as our funders request) champion its utility in all sorts of different sectors and in different ways – to promote cohesion, well being, bring jobs, investment, reduce recidivism, encourage empathy and good citizenship etc. etc.

First, I’m wondering if heritage can and should bear the weight of this obligation and indeed when and why did we start speaking about heritage as something that has to be productive; that should made to work, and work harder in times of austerity? Does the direction of this expectation bias the positive, ennobling, affirmative and comforting kinds of heritage over the disruptive, upsetting, confusing and awkward bits of the past? As well as warming our hearts and making us feel proud, should heritage also be granted the capacity to make us feel bad, ashamed, fearful, and concerned about the current state of the world and our previous recklessness and/or ignorance?

Liz Svencenko’s work establishing the International Coalition of Museums of Conscience is a great example with the explicit intention to use histories of oppression to provoke discussion about contemporary human rights. For an example on how uncomfortable histories can be locally sidelined see Mats Burnstron’s discussion of Buckeberg location of the Third Reich’s annual harvest festivals between 1933 and 1937 which give a sense of the massive popular support for the Nazi party. In all these efforts, my general concern is whether the growing demands placed on heritage becomes a way of deferring our own responsibility and obligation to make the world better, more equal etc.

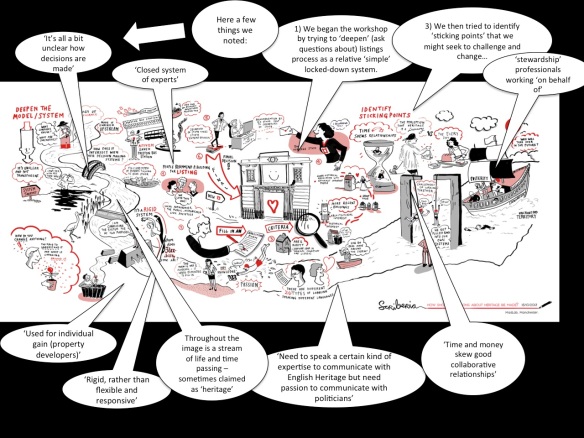

The second thing I’m wondering, and this echoes a phrase introduced by a fellow workshop participant, is whether the heritage system we have right now might be better described as ‘dysfunctional’ rather than ‘deficient’. Notions of blocking points or sticking points used to frame the workshop’s remit tend to carry with them negative connotations and assume that our efforts should be in trying to “free up” or “streamline” heritage decision making. This makes sense only if you buy into the idea that heritage is inherently good (egalitarian, consensus-driven, democratic) and that more of it would be better. If you hold a more critical view that heritage is a something that reflects and perpetuates powerful interests in all sorts of subtle and not so subtle ways then it would make sense to conceive of sticking points as useful, progressive, even emancipatory.

Rodney Harrison (2013) writes about a crisis of accumulation in heritage. He basically says there’s too much of it and that the rate of increase is unsustainable. Part of this is down to a kind of mission creep in a preservation sector that secretly longs for everything to fall under its purview and responds to critique with incremental rounds of inclusion. In the case of UNESCO, for instance, from its initial beginnings saving grand cultural monuments, to the subsequent inclusion of nature, to industrial history, working class history, multicultural history, intangible history… the solution has always been to extend the remit under a guise of being inclusive. Harrison doesn’t go as far as to say we should abandon heritage and list making altogether although there are some scholars that do just that. Michael Landzelius, for instance, in 2003 argued that the very term ‘heritage’ is unhelpful because it encourages essentialist thinking and notions of blood lineage, and entitlement that has so often been used to fuel and justify ethnic conflicts. He advocates a wholesale disinheritance and the subversive removal and relocation of historic buildings and objects. Instead, Harrison asks us “to forget in order to remember”; to regularly monitor and change that portfolio. Inevitably this means removing or at least finding another way to deal with heritage that applauds racism, sexism, elitism, colonialism and all the rest. The city of Berlin makes an attempt at this by breaking up the monumental form of some of Albert Speer’s buildings with strategically placed utilitarian road signs and mundane street furniture to try to deaden their symbolic effect.

Are there similar examples in the UK? Our current stock of heritage and examples of public memorialisation champions a set of messages that are often inappropriate. Monuments in every market town objectify women with depictions of naked mermaids and sirens and symbols of justice while strong fully clothed men have names, are real people and stand upright, tall and proud. Country houses celebrate wealth and colonialism and royal palaces cultivate our consent to a ruling elite who enjoy divine rights and benefit so much from the hereditary transfer of wealth. Similarly, industrial heritage might nod to worker exploitation and resistance but the emphasis so often ends up being perversely uplifting … about the dignity of the male worker, their triumph over nature, their technological ingenuity, the silent tolerance of hardship and their solidarity. The mission tends to be less about galvanizing people into action and more about securing tourism revenue and the part-time service jobs that come with it. These critiques have been made before by scholars and practitioners but they are still relevant and worth reiterating. My own work has explored similar themes on the silencing of the environmental; how industrial heritage so often presents mineral extraction as a heroic battle that took place in the past rather than something that continues today. It’s a tension that is really striking in Blaenavon and the Big Pit in Wales. A real success story on some measures. World Heritage recognition, lots of international tourists, a revamped commercial high street with book stores and coffee shops and some great and genuine and critical interpretation of the strikes and pit closures. But it’s almost as if the mining has stopped. The open cast pit operations all through the Welsh valleys are so frighteningly efficient these days that almost none of the wealth gets left behind.

So it is perhaps worth asking as part of this workshop whose interests are served by removing blocks and stops to heritage decision-making? Might our lubrication risk leading only to a more effective rolling out of the existing system? Might we be oiling the wheels of neo-liberal trickle-down economics that appropriates heritage as a front-line vehicle for gentrification?

If our goal is to make better heritage decisions we also, and I’m sure we will, discuss how “better” is defined and on who’s terms? Some technical questions might be: How has the application of such apparently objective listings criteria resulted in a portfolio so skewed to dominant groups and the messages they want to convey? Is there a bias in the very DNA of how we think about significance and go about trying to capture it? How, for example, do the formal architectural typologies we employ tilt the balance towards favoring one kind of building or another? There’s some fantastic work from the US by Barbara Little and Judith Wellman that shows how the peculiar quality of ‘integrity’ employed is often invoked by State Historic Preservation officers as a gatekeeper to control access to certain prestigious heritage lists. It means that the politics codified in the forms and technical protocols result in many kinds of women’s history, ethnic history and class history getting omitted and doubly silenced because they don’t tend to be as materially “solid” as the well kept remains of rich influential white men.

That takes us to the concept of value in the preservation and heritage sector, to the systems we employ to “detect” value, and how difficult decisions occur essentially because of disputes about value. I’m currently in the middle of my own AHRC research project comparing US and UK listing procedures to better understand how we locate value in the built environment and I’ve been finding Pierre Bourdieu’s work on cultural capital useful since he brings together concepts of value from political economy and aesthetic theory. I like the way he challenges the privileged status enjoyed by economics as a discipline that takes for granted the very foundations of the order it claims to analyze. I’m getting the sense that economics and business logics around value have the upper hand in the heritage sector. Even when we try to assert that there’s more to it, or we want to reject or resist commercial pressures, the vocabularies we use and the logics we employ are already corrupt. An example that comes to mind was the 2006 conference titled Capturing the Public Value of Heritage. I didn’t attend but an edited copy of the proceedings is on-line where Hewison and Holden (pages 14-18) set up what appears to be a quite reasonable and astute triangle of heritage values that gives equal weight to the intrinsic, instrumental, and the institutional. It struck me that the heritage object itself and its own inclinations to persist, or decay, or in various ways embrace or reject the meanings we inscribe upon it, does not feature as part of the decision making. While the latter two types of value are external to the object, even intrinsic value qualifies as value only in so far as it does something to us that we can recognize i.e. creates a human experience, prompts an emotional movement. Might there be other kinds of value that exist outside our own “value radar”? And should we not still accept that things have a right to exist even if they aren’t formally recognized by us as having value? Dave Clarke a UK geographer and Baudrillard scholar makes this point well when he calls value “a conceptual virus spread by modernity” that “accords to a logic of equivalence ensuring that everything can be evaluated and implying the desirability of annihilating everything that is valued negatively” (2010).

I think this problem in our use and application of value comes through strongly in the 2006 conference proceedings with its title “capturing value”. For me this “capturing” paints a picture of the heritage sector as something like an elaborate plumbing system improperly assembled by the experts so it leaks value out. The solution apparently – inevitably when framed like this – is that the public and politicians are brought in to find the leak and put value back into productive use. It reminds me of Franco’s totalitarian dream for Spanish irrigation where any drop of water that was allowed to enter the ocean was understood as a drop of water wasted.

Back in 1986 when Bourdieu published his essay on the forms of capital he mused about how it was odd that everything that escapes economics as a means of measuring quality (sophistication, aesthetic sensibility, cultural knowledge, taste, stylistic appreciation etc) was the virtual monopoly of the dominant social class. By now it seems that the logics of economics has so much orthodoxy that the dominant social class no longer even bother to keep up the pretence.

The second thing that surprised about the triangular model on the public value of heritage presented at the conference was how in all its reasonableness it advanced a transfer of power and influence away from heritage professionals. Instead of being seen as public servants, professionals and experts are set apart from the public as if acting in their own interests. Oddly, the same critique is not leveled at politicians because when explaining the heritage value triangle, Hewison tells us that there is a “democratic deficit” in heritage that might lead to “a real crisis of legitimacy”. Again, it’s clear who is singled out as being at fault. It is the professionals that are expected cultivate a more “authorizing environment”, and need to “re-validate themselves”. The published transcript of the proceedings make this position appear uncontested. Maybe there was an outcry in the room? Maybe everyone was seduced by the rhetorical force of the triangle diagram? Or maybe everyone was so worn down by the way market logics and entrepreneurial thinking have taken centre stage in the formation and delivery of public policy that model seemed appropriate and reasonable?

Thanks for getting though it all. I’m not sure this all adds up to a single coherent position. I’d welcome any comments, corrections about misconceptions, or requests for further clarity.